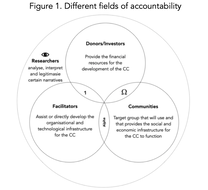

The sustainable development agenda has a special focus on people in vulnerable conditions. Adger and Winkels[1] argue that in order for development to be sustainable it is important to address the underlying components in vulnerable societies. Vulnerability is a complex concept that embeds different dimensions, some of them including aspects such as social relations, capabilities, assets, and social exclusion[2]. In consequence, it is worth analyzing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), from a vulnerability perspective. Using SDG wrapping as a point of departure, it is of interest in this document to reflect on some of the SDG indicators, specifically those with a focus on (digital) financial systems, which include banking, and credit availability (i.e Target 8.10). Financial systems support communities in (re)producing, distributing and accessing goods and services. Therefore, Target 8.10 could be interpreted as an attempt to stimulate the local markets through financial services. This interpretation of the underlying objective of the target, allows for exploring, or perhaps forking, alternatives that support the economic system and can be better held accountable for how they address vulnerable communities. An example of a financially inclusive solution coming from the business sector is micro-credits. Through this, financial service banks offer poor people access to cash liquidity but might also lock people in debt loops. From a vulnerability and resilience perspective, it is worth questioning if giving people access to credits is really building resilience capabilities or if these businesses are perpetuating vulnerability. Are the current targets of financial inclusion just a way of wrapping (framing) unsustainable practices into more "marketable” ones? An alternative coming from the grassroots is Complementary Currencies (CC), which are social technologies that create complementary monetary systems and aim to have economic and social benefits in the communities. CC can be designed for different purposes, for example to tackle social exclusion and unemployment, localize economies, and build social capital and civic commitment[3]. Today, several organizations are introducing digital CC in vulnerable communities, thus making them an interesting alternative for sustainable development. Surprisingly, they won’t necessarily have an impact on achieving the SDGs since this financial instrument won’t increase the number of ATMs in a region, or raise the amount of bank accounts in a community, which are the basic indicators for the financial inclusion component in the SDGs. CC leverages the strength of the local social, economic, and political infrastructures, therefore, to implement this social technology, it is important to develop the capabilities of the target communities. This process of implementation, financial, self-organization and social capabilities being developed, allows us to envision a potential increase in the community’s adaptive capacity, and hopefully a decrease in the community’s vulnerability. It is out of the scope of this document to describe in detail how these CC are being implemented, however, in line with the objective of this document, some reflections about how actors account for their implementation process might be in place. The development of CC is a complex endeavor that requires the interaction of different collective actors. Figure 1 presents four possible actors that interact in the development of the CC for development. These are: communities, donors/impact investors, facilitators, and observers (i.e Civil Society, NGO, Academia). Based on Fligstein and MacAdam[4] (2011), it is possible to argue that these collective actors, “interact with knowledge of one another under a set of common understandings about the purposes of the field, the relationships in the field (including who has power and why), and the field’s rules”. Actors are embedded in complex webs of fields[5] thus, are accountable to different stakeholders[6]. To construct these accountability frames, donors, facilitators, communities and observers make use of different frame constructs in the micro, meso, and macro level[7]. In this framing construction, accounting becomes an interpretative art[8] with a major role in shaping reality in order to create and maintain stable social worlds[9]. Accountancy becomes a construction of narratives in which hard numbers and soft language come to interplay. Digital currencies open the opportunity to represent performance both through the use of numbers, measures and statistics of impact, and through textualizations and contextualization of these numbers[10]. For example, facilitators frame strategic actions by highlighting the number of people that are being supported through the CC and developing emotional stories about why their solution is relevant to the world. Donors can communicate the number of people that are now eating “warm meals" thanks to their funds, attracting donors or impact investors. In one of the sessions held by the facilitators to train the community in implementing a CC, a community member claimed, “we will spend, spend, spend”, as an act of commitment to the project and thus increasing the number of local transactions to later be seen in the data. Finally, we the Observers, with our inquiry lenses analyze, reflect, discuss, make sense of these numbers, pictures, and texts. Through our knowledgeable accounts, we aim to inform the world about what is happening out there in reality. The question that motivated this document asked, “how does the SDG increase and/or shape accountability in the relevant field”? Well, they don’t. The accounts that the different actors develop, are constructing, redefining and contesting what the SDG are. The different CC actors transform (or wrap perhaps) the meaning of sustainability through their actions and later shape reality through their framing accounts. Realities, that hopefully, address the underlying components of vulnerability. [1] W. Neil Adger & Alexandra Winkels, 2014. "Vulnerability, poverty and sustaining well- being," Chapters, in: Giles Atkinson & Simon Dietz & Eric Neumayer & Matthew Agarwala (ed.), Handbook of Sustainable Development, chapter 13, pages 206-216, Edward Elgar Publishing. [2] Adger, W. N. (2006). Vulnerability. Global Environmental Change, 16(3), 268–281. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.006; FAO, “AnalysIng Resilience for better targeting and action” (2016); Frankenberger, T., Mueller M., Spangler T., and Alexander S. October 2013. Community Resilience: Conceptual Framework and Measurement Feed the Future Learning Agenda. Rockville, MD: Westat [3] Smith, A., Fressoli, M., & Thomas, H. (2014). Grassroots innovation movements: challenges and contributions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 114-124 [4] Fligstein, N., & MacAdam, D. (2012). A theory of fields. New York: Oxford University Press. [5] Ibid. [6] Lounsbury, M., M. Ventresca & Hirsch, P.M. 2003. Social movements, field frames and industry emergence: a cultural–political perspective on US recycling. Socio-economic Review, 1: 71–104 [7] Joep P. Cornelissen & Mirjam D. Werner (2014) Putting Framing in Perspective: A Review of Framing and Frame Analysis across the Management and Organizational Literature, The Academy of Management Annals, 8:1, 181-235, DOI: 10.1080/19416520.2014.875669 [8] Morgan, G. 1988. Accounting as reality construction: towards a new epistemology for accounting practice. Accounting, Organizations & Society, 13, 477-485. [9] Fligstein, N., & MacAdam, D. (2012). A theory of fields. New York: Oxford University Press. [10] Sandell N. & Svensson, P (2014). The Language of Failure: The Use of Accounts in Financial Reports International Journal of Business Communication

1 Comment

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed